- Home

- Andrew Feldman

Ernesto Page 9

Ernesto Read online

Page 9

The chair hit the deck of the boat and nearly tumbled into the water as Ernest stood up and, stumbling to the other side of the boat, tried to hold on to the rod that the fish was pulling from his hands. Ernest roared at Josie to “Bring the boat around!” rather uselessly, because he was already bringing the boat around. Clutching the seat back, Josie twisted his body to glare at Ernest (and to swear at him) while he piloted the boat in a new direction. Then on a gamble, Josie reached up and pulled the accelerator to kill the motor. They floated.

All was silent except the waves, the friction of the line, and the bearings spinning in Ernest’s reel. To their surprise, the fish was now swimming straight out behind the boat and dragging them as a tugboat drags a freight ship. They had attempted to chase him in the direction he had been choosing, but the fish had called their bluff, and they were now playing a game of tug-of-war with a fish at fifty fathoms at the other end of the rope. By turning the ship to follow the direction the fish was choosing, they brought the boat around so that they could get closer and closer during the better part of an hour. At intervals they could see a blurred outline shimmer as it passed beneath the waves. With growing confidence, Ernest pulled more forcefully to bring him in, but he backed off as he felt the fish’s great strength pull against the slackening line. “Then, astern of the boat and off to starboard, the calm of the ocean broke open and the great fish rose out of it, rising, shining dark blue and silver, seeming to come endlessly out of the water, unbelievable as his length and bulk rose out of the sea and into the air and seemed to hang there until he fell with a splash that drove the water up high and white.”24 Hanging on, Ernest watched in awe as the fish leaped from the water and bucked with all his savage, power, like a four-hundred-pound horse, hovering weightless for a suspended second as he jumped—sunlight gleaming across azure, silver, and indigo flanks.

The marlin leaped out of the water in ten long, clean jumps while, stunned, they watched the creature and gulped. He was magnificent. His sword was blue, and when he jumped, “it was like the whole sea was bursting open…The ocean was flat and empty where he had jumped but the circle made where the water had been broken was still widening.”25 His pointed scythe-like tail and great dorsal fin opened like a sail, and he jerked his head from side to side as he tried to shake the hook loose. Then the great weight of him crashed down…leaping and crashing, again and again, and throwing water like a racing motorboat as he staggered and surged ahead, fighting the unknown with every atom of courage, strength, and intelligence against an adversary at the other end that he had never seen, against the hook in his tongue, against the line between his teeth, against the deadly force behind him. They only noticed how long the fight had been when daytime turned to dusk.

In the sunset, the fish’s outlines appeared in the murky water, a shimmering casket whose misfortune they had drudged up from the deep. Finally they succeeded in bringing the boat close enough to put a gaff in, and as they collaborated to finish the crime, a cloud of shadowy blood fanned out and enveloped the great fish still in the water below. Grunting, Josie leaned in, grabbed the cable, and felt the full weight of the fish in his hands. When at first it did not budge, they heaved together until they managed to get him on board—he was longer than the width of their boat, they noticed ecstatically and nauseously. They stood over the quivering fish, studying the creature extracted from the ocean as it moved on to another place. The large eye stared back at them, full of rage, confusion, frustration, then fear, before becoming very still suddenly, frozen, and leaving nothing of its great spirit but silence.26

The tarnished silver body lying across the deck had meat for a hundred men. Conquering any lingering qualms for the killing of such a marvelous animal, they motored to port with their trophy of flesh and bone strapped across the bow. With jubilation, some envy, and much hunger, the Cuban fishermen in the port watched los americanos returning and congratulated them. Driving a steel hook into the marlin’s mouth, they lifted it upright with a cable and pulley on a thick timber crane at the end the dock. When they had washed the blood, they took their photographs, then watched as the knives went to work along the flesh to slice the steaks they would eat that evening. There was too much meat for the four of them to consume or store, but they would make good use of it at the market in Havana where it was selling for ten cents a pound.27 Soon they were giving some of it away to the people along docks who had helped them when they returned, simple people with hungry children at home. The jig hacked off the sword and plopped it into Ernest’s hands. After a second of hesitation, he broke into a watertight grin, and the old jig grinned back, returning to the carcass to cut the gringos’ steaks.

Before their feast there would be abundant rum at Sloppy Joe’s at the corner of Zuleta and Animas streets—a modest grocery store, converted to a tavern by José Abeal, an immigrant from Spain. This establishment was fast becoming one of the most well-known drinking destinations in the world. Its name, Sloppy Joe’s, came from the seafood its owner kept for patrons at the bar. When the ice invariably melted onto the floor below, it caused some of his American patrons to kid one afternoon, “Why, Joe, this place is certainly sloppy; just look at the filthy water running from underneath the counter onto the floor.”28 The name stuck. The joint also served a ropa vieja sandwich of pulled beef with creole tomato sauce called the “Sloppy Special,” whose bastardized American version appears in middle-school lunchrooms today. When Prohibition ended the following year, it was Ernest who had the bright idea to plagiarize the name from the Cuban bar, changing their Key West joint’s name from the Blind Pig to Sloppy Joe’s after the Old Havana establishment. The rebranding gave it an air of respectability and disassociated it from illicit activities.

After aperitifs at Joe’s, they would head just a block and a half away to La Zaragozana, where the capable chefs would grill their marlin steaks to delectable perfection.29 If the night before they had slept aboard the Anita, trading night watches like swashbuckling pirates or eunuch monks, that night they delegated the watch to an indigenous boy and celebrated in grand style, in all likelihood in the brothel backrooms along Merced and Economica streets, stumbling-distance from the old wharf. The “discreet” code word at the time for these establishments was “los clubes de sesenta y nueve”—“sixty-nine clubs.”30

In the tapestried and mirrored rooms of the red light district, “the prurient spot resorted to by courtesans,” explained T. Philip Terry, a popular travel writer at that time, a great variety of women were available, ranging in “complexion from peach white to coal black…15-year-old flappers and ebony antiques…who unblushingly loll about heavy-eyed and languorous…in abbreviated and diaphanous costumes; nictitating with incendiary eyes at passing masculinity; studiously displaying physical charms or luring the stranger by flaming words or maliciously imperious gestures.”31 Another travel writer, Sydney Clark, described Havana at that time as the place “where conscience takes a holiday.”32 “Ernest said he liked Cuba because they had both fishing and fucking there. I believe they had him try out all the houses of prostitution,” reported boat builder and angler John Rybovich, a longtime friend.33 In Havana at that time there were 7,400 prostitutes on patrol.34

Military judges had found Rubén de León, Ramiro Valdés Daussá, and Rafael Escalona guilty the previous week of a violation of an 1894 explosives ordinance law. On April 26, they sentenced the three youths to eight years in the sinister Príncipe Castle, an isolated prison on the Isle of Pines. When Marianao police and army officials had entered their shared house in the Almendares suburb, they found a cache of arms and ammunitions, and in a nearby garage, a car loaded with dynamite, rigged to detonate via remote control. The students’ intention had been to set off the explosives near President Machado. Per military police, this had been their sixth attempt to assassinate the president. Senator William E. Borah bemoaned the youths’ plight before the United States Senate on April 11, 1932. Throwing them in dungeons, Cuban authorities had not permitted

the students to see family or lawyers, which Cuban officials recognized to be true, but explained their sequestration was a necessary precaution to prevent further assassination plots.

Just a week before, on April 19, the police had found another car bomb at the home of Antonio Chivas, an engineering professor at the University of Havana: “An infernal machine which was in reality an automobile made into a monster bomb,” said the police report. Some “youths planned to abandon the car close to police headquarters so that when the handbrake was released to remove the car from the streets, the circuit would be closed, exploding the huge [350-pound] TNT charge, thus wrecking the headquarters building and killing the majority of police reserves quartered there.”35

* * *

—

After Ernest’s first week in Havana, a steamer emerged from the haze with vapor following her like a bridal train as she puffed and sputtered across the bay.36 Looking up from the paper, Ernest watched her now with anticipation as she came in, and he rose to greet her as the docks men attached a gangplank to her side, like an assembly of fathers giving their daughter away. Pauline’s hair had been newly styled for her arrival, and descending the catwalk in her finest apparel, she looked like a present that had been wrapped for Ernest’s birthday.37 Despite best intentions not to, she shivered when she finally stepped down and held him in her arms, happiness swelling in their throats during the first moments that they saw each other again.38

While the Anita trolled for fish along the coast with Pauline newly on board, police raids and bomb blast reprisals continued to spread fear throughout the city of Havana. Now a year and a half after the president shut down the press, the remaining newspapers no longer reported the news. Among abrupt notices of curfews, detentions, and disappearances, were fashion shows, casserole recipes, gossip columns, quaint stories of human interest, and interviews such as the one Ernest gave when approached by reporters along the docks. Mr. Hemingway, why have you come to Cuba this summer? “The Cuban coast offers one of the best fishing grounds in the world to the fisherman who is looking for big game. In three days of fishing we have caught four marlins and three sailfish, one of which was landed by Mrs. Hemingway.”39 If the interview makes the writer appear oblivious to the insurrection, it’s because broaching such subjects in the newspapers was simply not allowed. Conceivably still determined to write the story about revolutionaries that he had failed to finish, A New Slain Knight, Ernest wrote Perkins in May that his current research in Cuba was about much more than fish.40

After a few days out on the water with the boys, Pauline telephoned Jane Mason from her Ambos Mundos room.41 Jane would join them on the boat the following day. Then the Hemingways were invited for drinks at Mr. and Mrs. Mason’s home and, afterward, a proper initiation to Havana’s glamour spots.42

Pauline might have been just as taken with the Masons’ exquisiteness and money as her husband seemed to be. Jane was a perfect strawberry-blond beauty with an athletic body, crystalline eyes, and a racy disposition that contrasted strongly with her innocent visage and her husband’s dusty old money.43 Not only did Jane aim to have fun at all costs, but like the Fitzgeralds and the Murphys in Paris and on the Riviera, the Masons were beautiful people—multilingual and cultivated—as admired for their physical splendor as for their extravagant parties. Like the Murphys, they playfully and pretentiously collected books, paintings, and the artists that created them like feathers of exotic birds.

Jane was married to Grant Mason, Jr., an executive expanding Pan Am Airlines’ operations in the Caribbean and the heir to a sizeable family fortune. A good-looking graduate of Yale University, Grant was the charmed descendant of James Henry Smith, a successful Wall Street speculator. For her radiance, attractiveness, and style, Jane’s 1926 debut instantly made her an object of admiration. With “large eyes and fine features,” the lovely Jane Mason had “Madonna-like” qualities, accented by a middle part in her smoothed back pale-gold hair.44 During Jane’s visit to the nation’s capital, first lady Grace Coolidge called her “the prettiest girl ever to enter the White House.”45 Fond of sculpting, dancing, and singing, Jane Mason was a creative soul and patron of the arts and had opened her own art gallery in Havana. Her marriage to Grant had been the talk of the town, an event reported by more than thirty newspapers and magazines.46 Whatever the consequences, the Masons’ glamour and amusement would have been difficult for the Hemingways to resist.

After the day’s fishing, the Hemingways joined the Masons at their villa, recently erected in Jaimanitas, a suburb à la mode along the water at the outskirts of Havana. As a wobbly red sun dissolved insouciantly into the horizon, they sipped daiquiris prepared by Cuban servants and rested tired, sun-bronzed bodies in pool chairs on the terrace of the Masons’ extravagant home. Standing inside the sculpted stone banisters, the two couples chatted courteously, drank steadily, and took careful measure of each other.

When conversation waned, Grant pointed at a neighboring mansion across the way and said that it belonged to Ambassador Guggenheim. Then he showed them his forty-five-foot yacht, the Pelican II, anchored to a private pier at the end of a footpath from his stunning garden to the shining sea. Admiring the grounds, ship, sunset, and swaying water, the couples awaited the entrance of evening while breezes refreshed and restored their senses. When all was dark except for the tiki torches and the bright sparkling of the stars, the Masons joked that they should take a spin see the show at the Gran Casino Nacional, and throw some of their good money away.

* * *

—

After nearly a week in his wife’s company, Ernest accompanied her to the ferry station and watched her ship shrink in the distance and disappear. Fearful of the approaching May Day holiday, Pauline returned to Key West to recuperate and to check on the house and the children. Writing to Ernest every day as his weeklong fishing and writing expedition extended into months, she was ever supportive of his work and his adventures, devoted to his needs, interested in his hobbies, taking care of bills, errands, and trip planning, attempting to do whatever she could to give the space and freedom he required to thrive.47 Occasionally, her Catholic conscience did remind him: she had taken him from Hadley, so he was forever hers.48

That Cuban summer, Ernest fished fifty-four out of fifty-eight days, trolling the northern coast of an island paradise and often in Jane Mason’s company without the supervision of her husband or his wife.49 Pauline and Ernest’s fifth wedding anniversary came and went with him in Havana and her in Key West and nothing to commemorate the occasion except a congratulatory telegram from Jane to Pauline, and Ernest’s note in the ship’s log that he “saw largest tarpon I ever saw.”50

At first, Jane Mason’s growing closeness with Ernest appeared to be out in the open, for she communicated with both Hemingway “friends” frequently in gay and attentive letters—in much the same way Pauline had written letters addressed to both Ernest and Hadley back in during her “Pilar” days.51

While a brave blond bombshell spending hours at sea with one’s husband might sound like a wife’s worst nightmare, Pauline did not seem, at least initially, to view Jane Mason as a threat, treating her as a friend and leaving her unattended in Ernest’s company. The wealth and beauty seemed to inoculate both Hemingways at first. Besides, she must have been fine company in Havana. Pauline might have misguidedly placed her faith in her husband’s low tolerance for high-strung women and so believed that their relationship would be short lived.52

In all probability bipolar himself, Ernest came to intimately identify with and understand Jane’s capriciousness; she was his Zelda, a biographer would remark.53 His short story “A Way You’ll Never Be,” crafted during the “Jane period,” suggested identification with turbulent personalities; it was, he said, written “to cheer up a girl who was going crazy from day to day.”54 As Jane’s friend would later report, “Jane Mason not only drank a bit, but was one of the wildest, hairiest, most drinking, wrenching, sexy superwomen in the world.”55

> Though in theory Ernest liked the company of men, his increasing fame, smugness, swagger, and drunkenness were making it much more difficult for other men to remain in the same room as him. After ruptures with Sherwood Anderson (the manliest writer of all), Harold Loeb (the Princeton athlete), and Gertrude Stein (his matriarchal nemesis), Ernest began to quarrel with and lose of other “friends.” During a fishing trip when they were marooned on Dry Tortugas, Archie MacLeish recalled that he and Ernest consequently “saw a little too much of each other,” and many years later Archie remembered Ernest’s temper and attacks caused by Archie’s slow reaction to a fire aboard: “I told him somebody ought to prick his balloon and that led to ribald observations about my not having a big enough prick…That began eating at him and he went on and on and on from there.”56 Back in New York, Archie had written trying to patch things up, but their friendship would subsequently decline: “The thing that troubled me always was that you seemed to be on the defensive against me and not to trust me. I know that you do not believe in trusting people but I thought I had given you about every proof a man could of the fact of my very deep and now long-lasting affection and admiration for you and it puzzled me that you should be so ready to take offense at what I did.”57

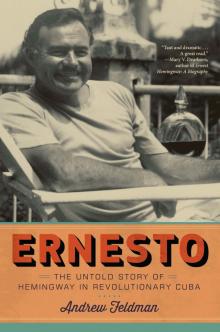

Ernesto

Ernesto