- Home

- Andrew Feldman

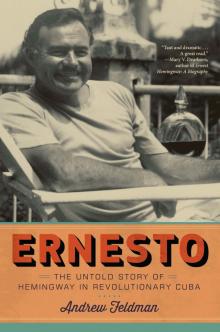

Ernesto

Ernesto Read online

ERNESTO

Copyright © 2019 by Andrew Feldman

First Melville House Printing: May 2019

Melville House Publishing

46 John Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

Suite 2000

16/18 Woodford Rd.

London E7 oHA

mhpbooks.com

@melvillehouse

Ebook design adapted from printed book design by Betty Lew

ISBN: 9781612196381

Ebook ISBN 9781612196398

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Feldman, Andrew, 1973- author.

Title: Ernesto : the untold story of Hemingway in revolutionary Cuba / Andrew Feldman.

Description: Brooklyn : Melville House, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018050528 (print) | LCCN 2018055010 (ebook) | ISBN 9781612196398 (reflowable) | ISBN 9781612196381 | ISBN 9781612196381 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781612196398 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hemingway, Ernest, 1899-1961–Homes and haunts–Cuba. | Hemingway, Ernest, 1899-1961–Knowledge–Cuba. | Authors, American–20th century–Biography. | Americans–Cuba–Biography.

Classification: LCC PS3515.E37 (ebook) | LCC PS3515.E37 Z5897 2019 (print) | DDC 813/.52–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018050528

v5.4

a

To my father, who challenged me,

To my mother, who accepted me,

To my wife, still standing her ground,

and to my daughter, que adora las sorpresas.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

1. Key West by Way of Havana, Newlyweds Passing Through (1928)

2. Oak Park and the War, Fathers and Sons (1899–1932)

3. Adventures as Close as Cuba (1932–1934)

4. An Island like a Ship (1934–1936)

5. A Romantic Getaway for Two in Civil-War Spain (1936–1939)

6. Hemingway’s Cuban Family (1939–1941)

7. Don Quixote vs. the Wolf Pack (1940–1944)

8. Hemingway Liberates the Ritz Hotel Bar and Pursues the Third Reich (1944)

9. The Return to the Isle of Paradise with Mrs. Mary Welsh Hemingway (1945–1948)

10. A Middle-Aged Author’s Obsession with a Young Italian Aristocrat (1947–1951)

11. A Citizen of Cojímar and a Cuban Nobel Prize (1951–1956)

12. A North American Writer and a Cuban Revolution (1956–1959)

13. New Year, New Government (1959–1960)

14. El Comandante Meets His Favorite Author (1960)

15. Hemingway Never Left Cuba: A Lion’s Suicide (1960–1961)

16. Finca Vigía Becomes the Finca Vigía Museum (1960–Present)

Afterword: When Your Neighbor Is Ernest Hemingway: Cojímar and San Francisco de Paula Today

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION

Along the windswept banks of a fishing village a few miles from Havana, there is a bust dedicated to the memory of a writer, set there by its inhabitants, the fishermen of Cojímar. When they first heard the news that Hemingway was dead, it felt as if they had received a blow from the long beam of their sail as wind changed and the boat came suddenly about. Still, some of them doubted the validity of the news; after all, the papers had declared his death on more than one occasion and were obliged to retract their stories when Mr. Way (as many of the fishermen, finding his full name difficult to pronounce, called him) returned from the dead, indestructible and immortal, like some hero of ancient lore.1 Others, sneering at the headlines, rejected the suggestion, repeating itself like a vulgar joke in the newspapers and on the radio, that his death had been a suicide. In this way, they were able for a time to maintain the fiction that their friend, Ernest Hemingway, was alive and that he had never faltered in the face of death.

For thirty years, the villagers had shared the sea and fished with Hemingway, so they believed that they knew him well. They came to love him naturally and simply, like a brother, as was their custom, and he came to love them back. Whenever he, in his motored craft, encountered them after a long day of fishing, rowing back beneath the sun, el americano would throw out a line and tow their boats back to port. Often, he would invite them for a drink in La Terraza, the village restaurant-bar beside the docks where they could talk, exchange tips about sea conditions, and enjoy some rum and one another’s company. Asking many questions, Ernest Hemingway, the writer, listened intently to their responses, to their sentiments, and to their manner of speaking—slowly gathering details for his work and strengthening ties of friendship with these men.

In Cojímar where his first mate Gregorio Fuentes also lived, Hemingway kept his boat, the Pilar. It was safe there. Everyone in the village knew who owned it, and they looked after it as if it were their own. As the years passed, he had become part of their community; when Gregorio Fuentes’s daughters married, Hemingway, along with the other fishermen, attended their weddings.2

* * *

—

Hemingway’s experiences in Cojímar provided the material that allowed him to write the novel that rescued his career and restored his readers’ faith in his astonishing talent. His previous novel, Across the River and into the Trees, had been considered a failure. This awkward work of “fiction” indulgently explored two of his infatuations: his World War I wounds and nineteen-year-old Venetian beauty Adriana Ivancich, with whom he had become enamored while deep in the throes of a middle-age crisis. The book was ill received by both the public and his critics, who ridiculed its self-indulgent style, gossiped about the disgraceful goings-on of its aging author, and declared his career over. Like a counterpunch, Hemingway then released a much shorter work, over a decade in the making, condensing his experiences accumulated during a lifetime of fishing the Gulf Stream—with the fishermen he had come to admire. He called this novella, about an aging fisherman and his Cuban village of Cojímar, The Old Man and the Sea.

The work achieved immediate success and widespread praise from many of the very critics who had so roughly criticized his previous work. It won him a Pulitzer Prize and, one year later, resulted in the achievement of literature’s highest honor, the Nobel Prize—solidifying his place as a literary legend. Recognizing his debt to the village and to Cuba, Hemingway immediately announced to the press that he had won the prize “as a citizen of Cojímar…as a Cubano sato.”3 It was a gesture that ran countercurrent to prevailing politics of his day, one that underlined his respect for the Cuban people and affirmed his identity as a world citizen and a member of the Caribbean community in which he lived. Keeping a promise that he had made to himself and to an old friend, he donated his prize medal to the church of La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, the people’s patron saint who, Cubans believe, possesses the supernatural power to grant or to withhold great favors.4 His gift not only underlined his gratitude but also suggested that, after twenty-two years of residence in Cuba, Hemingway believed in La Virgen too.

In the pages of Life magazine, The Old Man and the Sea first appeared with pictures of Hemingway walking along the shores of Cojímar village on its cover. Warner Brothers offered Hemingway $150,000 for the movie rights and another $75,000 to serve as the film’s technical advisor, an unprecedented sum for a writer to receive in 1953.5 Drawing from the film’s $5 million budget, the author also insisted upon employing all of Cojímar’s fishermen to assist in the production, in order to lend the film some authenticity, to recognize them, and to bring their struggling families some much-needed income.

Hemingway Dead of Shotgun

Wound; Wife Says He Was Cleaning Weapon,” said the newspaper, which Cojímar’s fishermen read before wrapping it around the baitfish that they would bring on the boat that day.6 Reflecting upon it, they saw Mary’s denial was merely her grief, and after long hours spent at sea, the realization that they were also grieving floated slowly to the surface. When they returned to port and observed his ship, the Pilar, anchored there, floating without a captain, their throats thickened from the emptiness, for they understood they missed a friend and a man that they had admired. They could not bring themselves to judge this man that they respected and loved. Gathering at La Terraza, they stood silently along the bar where their friend no longer appeared. But they wanted to do something more to honor him.

They decided to commission a sculpture and place it at the entrance of the harbor of their town. They were very poor, and they did not have enough money to purchase the material, so they melted down the propellers from their boats for a sculptor to fashion into a bust. Today the bust remains, its eyes fixed forever, gazing into the waters of the Gulf, a source of life and mystery that the writer loved and so often wrote about.

As a Hemingway scholar completing my dissertation at the Université de Paris IV, La Sorbonne, and following my research in Spain, I stumbled upon a story of Hemingway’s friendship with America’s persistent enemy. Then I read an article in a French newspaper announcing that the Finca Vigía Museum in Havana would be opening its doors and archives to foreign researchers like me. Following Hemingway’s example, I wanted to “go to the source” to investigate.

What I found there was an untold and remarkable story of Hemingway in Cuba, which has been eclipsed by fifty-seven years of Cold War blockade. The blockade, which continues to this day, has defined Cuban-American relations for the last half century and has had many regrettable consequences: it severed many of our cultural, intellectual, familial, and economic ties, and the prolonged separation has complicated our capacity to understand each other and the history that we “Americans” inevitably share. As Hemingway’s own story shows, the difficult lessons are not received easily, but those lessons are invaluable when attained in struggle against our own wayward natures—over time.

As the first North American permitted to study in residence at the Finca Vigía Museum and Research Center, I spent two years conducting interviews and examining documents that had previously been unavailable to other researchers. My investigations bore many fruitful discoveries, and when I myself “became Cuban,” through marriage, I believe that my perspective increased and continues increasing, a little each day, and in ways that I hope will add depth to this narrative.

Formerly, numerous respected researchers, unable to consult Cuban sources, had concluded that Hemingway lived in Cuba in isolation, as an expatriate American writer who did not associate with the Cuban people; yet my research in that country in consultation with Cuban sources revealed a completely different Hemingway, one who enjoyed a long and enriching friendship with Cuban fishermen like Gregorio Fuentes and Carlos Gutierrez, and with Cuban writers like Enrique Serpa and Fernando G. Campoamor, as well as an enduring affair and tender friendship with Leopoldina Rodríguez.

In Cuba, it is often said that Hemingway loved Cuba and that Cuba loved him back, and everywhere one goes in Havana this emotion appears in plaques that pay homage to the author, in statues, in Cojímar, in Habana Vieja’s Floridita Bar, at the Bodeguita del Medio, at the “Marina Hemingway,” in the affection with which Cubans speak of him, and in the way they maintain his boat, the Pilar, and his Finca Vigía home—as a monument and as a museum—as a shrine to the friendship that might have been.7

CHAPTER 1

Key West by Way of Havana, Newlyweds Passing Through (1928)

The long steamship lumbered and crashed over the shifting swells of a dark and turbulent sea. Two quadruple-expansion engines burned in the hull, turning twin screws, and heaving 9,266 tons and 485 feet of steel forward. Mile after mile, she plunged ahead.1 If it were not for the smokestack on her back, billowing clouds of smoke into the air, one might have mistaken her for a whale leaping amidst the waves, or a ghost wandering among the black dunes of the sea. Thunder cracked, and after a heartbeat, lightning spread through the sky and lashed the waves. Lying in the narrow beds of their cramped quarters, Mr. and Mrs. Hemingway and the other 802 passengers aboard the Royal Mail Steamer Orita closed their eyes, murmured their prayers, and attempted to fall asleep as the ship tumbled over the rollercoaster crosscurrents of the great Atlantic Ocean.2

In the morning, the wind and the rain were gone. A single drop fell from a faucet and splashed into a wash basin—like a period punctuating the silence after the storm. Illuminating the floating dust, the first rays of daylight traversed a quietly creaking cabin. The bulkheads and bed sheets were gleaming as white as the new places and life awaiting Ernest and Pauline Hemingway. As the ship slowed, Ernest’s eyelids flickered, then opened as he glanced about the cabin and got his bearings.

Grinning as he came to his feet, he slipped into trousers, while in the bunk beside him, his wife, Pauline, slept. It was a new day dawning, and he would soon be arriving in a place he had never been.3 An early riser ordinarily, Pauline was exhausted by her sixth month of pregnancy and by weeks of rough seas.4 Back in America, she hoped to deliver a baby soon, her first and her husband’s second, in the safe haven of her family home in Piggott, Arkansas. It was a town that, for all intents and purposes, her family, the Pfeiffers, owned. After a stopover in Havana, they would continue to Key West, then overland to Arkansas.

Shutting the cabin door softly behind him, Ernest stepped out into the humming corridor. Following the curve along the steel bulkhead, he found the hatch to the exterior deck. Leaning over the railing and breathing the air, wild and alive with the sea, he first gazed upon the shores that a Genoese explorer called “the most beautiful land that human eyes had ever seen” on the day he encountered a “New World.”5 Later, when Ernest neared the end of his days on Cuba, he would write that “all things to be truly wicked must start from an innocence.”6 And so it must have started as the first explorer peered down his telescope to survey brown bodies cutting across the hazy waters of a promised land. With “good bodies and handsome features,” the natives emerged “naked, tawny and full of wonder” from huts of littoral villages to swim out and greet the big boats arriving from the sea.7

Cocking their heads at the strange-talking men, the Taíno, Guanahatabey, and Ciboney offered parrots, spears, balls of cotton, and food and extended their hands in friendship.8 Their beauty, affection, and freedom from material possessions at first enchanted Columbus and his crew. But when the explorers saw their gold ornaments and inferior weapons, they seized them as their prisoners and ordered to be taken to the gold.9 The captain christened the island “Juana,” the name of the royal princess, and claimed it for the Spanish throne.10 Before he and his men had finished their conquest of the island, they would have exterminated approximately 8 million souls.11

As night fell and the ship approached the port, Hemingway could feel the engines shift, grumbling in a lower gear, and smell the scent of land. Their steamship rounded a peninsula and he could see the old Spanish fortress, the Castle of the Three Kings, on the hill.12 In the semidarkness, buoys clanged and moaned out in the bay. In the moonlight as he drifted by, Hemingway could see the stone garrets and high walls, which King Charles V of Spain had ordered built after the misadventure of Colón to protect his wealth as his colony grew.13

At the mouth of the harbor, sailboats, tugboats, and rowboats deftly intermingled, returning to port from the open sea. Black and copper-skinned men rowed weather-beaten skiffs, gathered lines, and recast them into the current with a persistent rhythm. Four centuries after Columbus, the natives had changed. Unseen in the eventide, their wrinkled faces now contained the features from not only Taíno ancestors but also of Iberian, African, and Eurasian peoples immigrating freely and under duress to another land.14 When the steamer plowed by bene

ath the moon, their eyes flashed as they took stock of the ship and the bulky author leaning over the railing of its upper deck framed by electric lights. More prudent than their great-great-grandparents, these natives maintained a distance, resigning themselves to the ritual of their daily bread.

Flirting with the salty-sour air of the sea, breezes scented with mangoes and mariposas came overland from the island’s interior, greeting another arrival with their sickly-sweet promise.

In the distance overhead, seagulls cried as the ship turned and a citadel came into view. Holding their position beneath the stars, the massive fortresses known to Habaneros as El Morro and La Cabaña sprawled across a two-hundred-foot hill and conquered the horizon.15 Throughout the Colonial Era, these fortifications had permitted the Spanish to control the harbor (although they would lose it to the British for a year from 1792 to 1793). The American Army seized control of the fortress and the island in 1898, when Spain lost the Spanish-American War. Later, Cuban dictators as diverse and as similar as Machado, Batista, Castro, and Guevara would make consistent use of the fort’s labyrinth of stone chambers to imprison their abundant enemies. on the spine of the peninsula above the fortress called La Cabaña, the Christ of Havana watched over the old city, raising a stone hand to bless arrivals while his wrinkled brow expressed some measure of hesitation. Having just converted to Catholicism to marry Pauline, Ernest noted the Divine Trinity in the statue’s extended index finger, middle finger, and folded thumb. Before the time of Christ, the gesture had evoked a trinity in a supernatural family—a mother, a son, and a spirit of light—in Aphrodite, Zeus, and Chronos—Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn—terrestrial beings and celestial sources, mystical origins in the stars, a falling, an isolation, and an aspiration to return. As he ascended in the literary world, Ernest included an epitaph serving also as title for his first novel, The Sun Also Rises: “One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth forever. The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose” (Ecclesiastes 1:4–7).

Ernesto

Ernesto