- Home

- Andrew Feldman

Ernesto Page 34

Ernesto Read online

Page 34

From the end of March until the middle of May, Anselmo Alliegro, a senator and president of the Cuban Congress, called for a compromise, appointing a bicameral commission to engage in discussions with members of the opposition to overcome the nation’s current impasse. Skeptical of the commission’s capacity to guarantee a fair election, M-26-7 and the Orthodox Party rejected these initiatives. At the end of March, Batista, heavily guarded, attended the opening of a new refinery for Shell Oil, insisting that the mountain guerrillas had been eradicated, and attended a glitzy party with his wife in a sequined dress, his cabinet in tails, and several leading members of the Mob smirking as they shook his hand at the grand opening of the $24 million, 572-room, 25-floor Havana Hilton on March 22 at the corner of Twenty-Three and L, also known as La Rampa, because it towers over the rest of Vedado.

* * *

—

As Havana glued itself to the radio, rumors buzzed, and speculation simmered among the staff of the kitchen at the Finca Vigía. But like many Cubans, Ernest Hemingway had been trying to get on with his own life. Fighting through the consequences of concussions, and the medicinal haze to treat them and other illnesses, he filed his taxes, answered four hundred letters, and growled at visitors whenever they unexpectedly appeared. That spring Ernest attempted something new and difficult: giving up hard alcohol for his writing, for his health, and for his wife. Off the sauce, Papa wrote to “Hotchenroll,” Ed Hotchner, that he had his weight down to 210 pounds and blood pressure to 140 over 68: “The reason before I didn’t write and Mary did was that was working over the ears and writing has been difficult. Had last drink of hard liquor on March 5th. Will not bore you with the details. It is about as much fun as driving a racing motor car without lubrification for a while. A good car that you know well and just what it takes to lubricate and just what it can do with lubrification.”53

When a Miss Phoebe Adams, a flirtatious editor in a floppy red straw hat turned up at the Finca requesting fiction for the Atlantic Monthly’s hundred-year anniversary, he granted her godforsaken wish by churning out “Get a Seeing-Eyed Dog” and “Man of the World”—two stories that would have benefited from further revision and seemed to express a growing fear that his injuries and ailments were causing him to go blind—for one thousand dollars apiece.54 In the first story, a man sullenly insisting on spelling the title term with a d sends his wife away so that he can get used to a “Seeing-eye[d] dog” on his own. In “Man of the World,” an old man who haunts gambling joints in Nevada loses his eyesight in a brawl, then routinely insists on taking a twenty-five-cent cut from whomever he hears winning at slots.

When majordomo René Villarreal brought the girl he would marry, Elpidia, or “Fanny,” to the Finca, Ernest took a break from struggling with sentences in his bedroom to ogle the pretty young lady with black hair and a beautiful smile, and to congratulate them. “Cuida bien de mi hijo Cubano” (“Take care of my Cuban son”), he told Fanny, and the next day when René brought in his mail, he said, “Your fiancée seems like a wonderful girl. You know you can move to the bungalow if you want. That way, you’ll always be close to her.”

“Thank you, Papa, but we already rented an apartment very close. It’s just outside the Finca. I can see the pine tree path from our window.”

“You can take the bungalow and save on the rent. Miss Mary and I always want you to be close. You can always move into the house when we’re away.”55

It was a generous offer that the couple politely refused. Fanny got pregnant, and they lost their firstborn before the end of that year. When René came to work as usual that week, Ernest ordered him to go home and be with his wife. His first responsibility was to his wife and family, said Papa; time would heal their wounds, but they had to console and take care of each other.

Ernest’s first son, Jack, had also moved down to Havana that year with his wife, Puck, and their two daughters to work for a brokerage firm. Unintentionally, wrote Mary, she and Ernest had given them less attention than planned, though she had babysat the girls, their animals, and plants when Jack fell ill with hepatitis.56

* * *

—

For the attack on the presidential palace and Radio Reloj, reprisals continued the following month. On April 20, Colonel Esteban Ventura Novo and his men from Batista’s secret service burst into apartment 201 of 7 Humboldt Street and slayed four youths for their suspected involvement: Fructuoso Rodríguez (who succeeded Echeverría as the president of the FEU and one of the founders of the DRE), Joe Westbrook Rosales (founding member of the DRE), José Machado Rodríguez, and Juan Pedro Carbó Serviá (also wanted for the killing of Colonel Antonio Blanco Rico). On April 23, Robert Taber from CBS News became the second American journalist to interview Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra for a television broadcast.

In May, the urban rebels responded to the Humboldt Street massacre with a bombing campaign in and around Havana—with eighteen exploding in one evening—on May 5. Five days later, the Urgency Court of Santiago tried 115 suspects en masse for participation in the Granma expedition, or the November 30 uprising; 40 rebels were sentenced to one to eight years, including 22 who had landed with the Granma, and the other 75 were acquitted and released—among them was key M-26-7 organizer, Frank País.57 During the verdict, a dissenting judge, Manuel Urrutia Lleó, defended the insurgents. He would later become the first provisional president under the revolutionary government. On May 19, Taber’s documentary, “Rebels of the Sierra Maestra: The Story of Cuba’s Jungle Fighters” aired on CBS, building on Herbert Matthew’s flattering portrayal of Fidel. On May 27, Taber published the same material in an illustrated article in Life Magazine, one day later in Bohemia, and two days later in Life en Español. These articles and news programs, in which Castro reiterated that he was not a Communist, were viewed by millions of people.

Under pressure from American press and displeased with the American ambassador’s mismanagement of Cuban affairs, the State Department retired Ambassador Gardner on May 14 and sent in Earl E. T. Smith as a replacement in June. Smith was a war hero, an Eisenhower intimate, and a former businessman who did not speak a lick of Spanish; his ability to stop a long-accumulating rebellion in progress would prove limited.58

At the time, the Cuban economy was not raising the standard of living for Cubans while foreign profit and corruption were running rampant. On May 26, 1957, Carteles, a Cuban magazine reported that twenty members of Batista’s government had bank accounts in Switzerland with deposits of more than $1 million apiece. In addition, American investors were making a profit of $77 million annually from Cuban holdings, but only employing a little over 1 percent of the Cuban population. On the day the article appeared, rebels crippled the massive Tinguaro Sugar Mill in Matanzas with a bomb.59

Two days later, a force of twenty-seven Ortodoxo insurgents financed by former president Prío and led by Calixto Sánchez White, the former president of the Cuban Pilots’ Association and suspect in the presidential palace attack, left the Bay of Biscayne aboard an eighty-foot yacht, the Corinthia, and landed at Cabonico. Their fate became a subject of controversy as the government, under the direction of Colonel Cowley, reported capturing 5 and killing 16 while the invaders said they landed 150 men who split into three groups that later incorporated themselves with Fidel’s men.60

Conscripted by Frank País’s 26th of July Movement in Santiago, fifty fresh recruits had been incorporated into Fidel’s guerrilla force in the Sierra Maestra in March. Under the rigors of training, foraging, and constantly moving through the jungle, some of the new recruits quit, but those who stayed on grew lean and hungry for action. To distract Batista’s attention away from the Corinthian landing to the North, Fidel and Che plotted what to attack next. Che had been hankering to pounce on the convoys full of soldiers whom they had been observing passing regularly on a nearby road, but with reliable intelligence from an ally in the government, Fidel thought it shrewder to take El Uvero garrison.61

Pitting eighty re

bels against fifty-three Rural Guard soldiers, the surprise attack, lasting three hours on May 28, marked a significant win for the rebels. From the perspective of “El Che,” it was a turning point: “For us, it was a victory that meant our guerrillas had reached full maturity. From this moment on, our morale increased enormously, our determination and hope for victory also increased, and though the months that followed were a hard test, we now had the key to the secret of how to beat the enemy.”62 Subsequent to the attack, Fidel promoted Che to comandante and gave him control of a column of guerrilla troops. That same day, urban terrorists detonated a bomb, shut down the grid of Havana Electric Company, and left the capital without power for two days.

* * *

—

In the eye of a revolutionary storm striking Cuba once again, Ernest, standing in his bedroom beside the bookshelf, and sitting barefoot at the table beneath the thatched arbor beside the swimming pool, had begun to put Paris to paper. In the days when “there was no money to buy books,” you borrowed them from Shakespeare and Company, “the library and bookstore of Sylvia Beach at 12 rue de l’Odéon. On a cold windswept street, this was a lovely, warm, cheerful place with a big stove in winter, tables and shelves of books, new books in the window, and photographs on the wall of famous writers both dead and living.”63

It was in Paris that he had discovered he could write about a place better when in another: he called it “transplanting” (a gardening technique) and supposed it could be “as necessary with people as it is with other sorts of growing things.”64 And now he was in Cuba, writing the story of Paris, of his own awakening in the cafés along the Seine where he had learned to do what he loved—writing stories like “Big Two-Hearted River” and “Up in Michigan.”

Looking up, then at the farm in front of him in Cuba, there was the swimming pool, the quail drinking in the pool, the lizards living and hunting in the arbor overhead, and the strange and lovely birds always living on the farm, the smell of jasmine and the blossoms of the framboyan, and the eighteen kinds of mangoes, the boy who had started transplanting in Oak Park in books, who found his father on Walloon Lake, who put pen to paper in upper Michigan without success, who had seen Cézannes in the Musée du Luxembourg, the horrors of war in Italy and Spain, the heights of life and death in Kilimanjaro, what a man could endure in Cojímar, and the Stream, and then he had returned to his island to paint his Paris with incomparable clarity.65 The confessions of the narrative ached with nostalgia. As he aged—far too rapidly—Hemingway reflected on his origins, and painfully remembered the sins he had committed as a young man, because of ambition: betrayals of first wife, Hadley, and of himself for pride; the loss of his first family; Paris, and the magic…it was gone now, but there was a part of it he could hold onto, forever, if he could just get the words right. Could he still see how good it was as he wrote it? Or as he read it back the next day?

While a writer who had just turned fifty-eight chased eternity in the hills above Havana, eternity was also chasing a twenty-three-year-old rebel leader, Frank País. Having just been informed that he was being followed, País had fled with Raúl Pujol Arencibia to a “safehouse” that was not safe. Betrayed by an informant, they were shot in the back of the head by Colonel José Salas Cañizares, chief of police in Santiago de Cuba. Joining many other young men like José Antonio Echeverría who had hoped for freedom and fair play, they became martyrs para siempre.66 His brother had met the same fate a month before. It is estimated that sixty thousand santiagueros attended the funeral the following day and continued to protest his murder in a general strike that shut Santiago down for three days during the US ambassador’s first trip to the city. The following month, the Cuban secret service made dozens of arrests.

On August 20, a column of fifty men led by Fidel Castro took an outpost manned by one hundred Cuban soldiers at Palma Mocha in the Las Cuevas region. Three days later, the film version of The Sun Also Rises was released. The rights had been purchased by producer Darryl Zanuck. It was directed by Henry King with screenplay by Peter Viertel, starring Ava Gardner, Tyrone Power, Errol Flynn, Mel Ferrer, and Robert Evans. Much to the producer’s disappointment before the picture’s release, Hemingway had disparaged it to the press by telling them that the film was “so disappointing” that he walked out twenty-five minutes into it. Mr. Zanuck, who made $1,500,000 in revenue during the film’s first year, fired back: “I tell you what happened…He was paid $15,000 by a third party for the book, and [we] bought it from that party for $150,000…Maybe that’s one of the reasons Mr. Hemingway is sore. That’s not my fault…I don’t think he saw the picture. I think someone told him about it. He doesn’t have the right to destroy us publicly for something he’s been paid money for.”67 Having given all rights to his first novel and film to his first wife, the writer did not stand to benefit financially from its success.

In a constant state of fear and revulsion, Cubans were weary of the dictator who was ruling their island and in favor of any alternative. Bringing the reality of the situation home, René Villarreal’s childhood friend from San Francisco de Paula, Guido Pérez, had been found tortured and murdered. In another instance, René’s brother, Luis, came home from his job at the mineral water company during the middle of the day with his cap in his hand, so René knew something was wrong. Their sister-in-law, Chela, had told him that her husband (their brother), Helio, had not been home all night. Their mother became very anxious when a body matching Helio’s description was found in an abandoned lot in Havana. Papa saw the troubled faces and asked what was wrong. Then he instructed Juan to take René and Luis to the morgue to see if it was their brother’s body. The person lying on the table had been tortured—he had broken fingers, stab wounds to the chest, and a quemarropa [clothes-burner] .22 caliber police-pistol shot through his chest at point-blank range. It was said that the police placed a burner beneath a chair to burn their victims slowly when they wanted to extract a confession, and the genitals of the man they saw were badly burned—but it was not their brother. When Helio, who had a reputation as a womanizer, turned up late the next day after a night of drinking, his relieved family gave him a thorough scolding.

Even closer to home, one dark night, Mary, Ernest, and René were awakened by the frantic barking of their dogs. Parking one jeep in front of the Finca Vigía and another in front of the Steinharts’ house, about nine Cuban soldiers in khaki uniforms were approaching the house. Upset by the intrusion, Hemingway, meeting them at the stairs, asked, “What are you looking for?! What are you doing on my property?!” The soldiers, looking tired and reeking of alcohol, responded that they were looking for “jóvenes revolucionarios.” “There are no revolucionarios,” said the author. “Leave my property immediately.”68 Skulking off, the soldiers were followed by barking dogs to the entrance. “Esos hijos de puta—probably wanted money to get more drunk!” said Hemingway, beside himself.69 The following day, one of the Hemingways’ dogs, Muchakos, did not show up to breakfast, and René found his body hidden behind the trees with his skull crushed by the butt of a rifle. “Those animals!” Hemingway said, and tried to report them to their superiors, requesting support from the US embassy to bring the soldiers to justice, but nothing came of it.

As September turned to October 1957, the Hemingways travelled to New York City, staying at the Westbury Hotel, in the company of African game warden Denis Zaphiro, for four months. There, Ernest would join Ed Hotchner to watch Carmine Basilio win the middleweight championship against Sugar Ray Robinson and the first two games of the World Series between the Braves and the Yankees at Yankee Stadium. When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I and II into the stratosphere in October and November, many Americans fretted that the Russians were winning the “space race,” but Ernest was not perturbed. It might motivate the United States to spend more dough on science, he said.

At the end of the preceding summer, Gregory had been admitted into Miami Medical Center, diagnosed with schizophrenia and administered electric shock treatm

ents. When his son wrote him on August 20, “Sorry that I got into this shape, but I will be out of here soon,” his father called the hospital, spoke with his son’s doctors, and arranged to take care of the bill as his son had requested. “They say that treatment cannot possibly do your brain any harm…We want to do everything that can be done to make you well, Gig. Do you have a good radio?”70 In the middle of October when he was released, Ernest flew up to Miami to retrieve him from the hospital, driving with him as far as Key West in a rented car and giving him a ticket to Cuba. Instead of taking the flight, Greg cashed the ticket in and never saw his father again.

* * *

—

In the middle of October, leaders of vying factions like the Authentic Party, Orthodox Party, Revolutionary Directorate, M-26-7, Revolutionary Workers Directorate, and Democrats announced the formation of the Cuban Liberation Junta, setting aside differences to bring about the overthrow of Fulgencio Batista. There was a growing tension between members of the Miami Pact devised by the junta and the Sierra Maestra Pact that Castro had worked out with Raúl Chibás and Felipe Pazos in July. (Coincidentally, Pazos’s eleven-year-old son, Felipe, Jr., played mandolin alongside Spencer Tracy in The Old Man and the Sea.) Feeling that ex-president Prío’s endgame was to return himself to power, Castro would renounce any obligations to the junta in December and inform them that he had already designated Manuel Urrutia Lleó as provisional president.

In November, the opulent Hotel Capri and Casino, owned by mobster Santos Trafficante Jr., opened two blocks down the street from the Hotel Nacional, and Che Guevara began publishing an illicit newspaper to run counterculture to the national press: “As for the dissemination of our ideas, first we started a small newspaper, El Cubano Libre [The Free Cuban]…We had a mimeograph machine brought up to us from the cities, on which the paper was printed.”71 On November 10, Ed Hotchner’s television adaptation of Hemingway’s short stories, The World of Nick Adams, premiered on CBS and received mostly positive reviews.

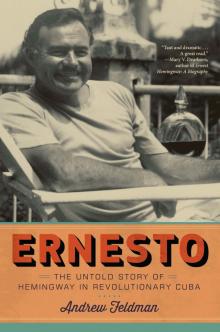

Ernesto

Ernesto