- Home

- Andrew Feldman

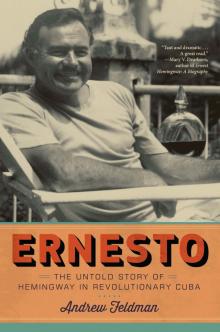

Ernesto Page 26

Ernesto Read online

Page 26

Mary and Ernest enjoy an evening at El Floridita Bar with friends. On the left side of the bar, Roberto Herrera is smoking and speaking. Immediately next to Hemingway, actor Spencer Tracey sits listening in a jacket and tie. (Courtesy of Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston and Finca Vigía Collection)

Ernest attends “America” Fuentes’s wedding. America was one of the daughters of his first mate, Gregorio Fuentes. (Courtesy of the America Fuentes Collection)

Hemingway casts a dragnet with Cojímar children. (Courtesy of Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston and Finca Vigía Collection)

Mary Hemingway took this picture of their Majordomo, René Villarreal, in 1957, when he introduced his fiancée, Elpidia “Fanny” Rodríguez to Ernest at the Finca Vigía. Even though it was a chilly day, Hemingway was wearing shorts, so Mary took the photo from the waist up. (Courtesy of the Villarreal Family Collection)

To promote tourism on the island and meet the author, Fidel Castro and Che Guevarra participate in Hemingway’s Marlin-fishing tournament. (Courtesy of Finca Vigía Collection)

Ernest and the Director of the Cuban Institute of Sports, Physical Education, and Recreation present Fidel Castro with trophies after the author’s fishing tournament. (Courtesy of Finca Vigía Collection)

A bartender prepares a daiquiri in front of Hemingway’s statue at El Floridita Bar. (Franklin Reyes / Associated Press)

* * *

—

The Dominican Republic’s president and military strongman Rafael Trujillo ruled as dictator from February 1930 to May 1961. “El Jefe” or “El Benefactor,” Trujillo was mixed race, like Batista, yet made a reputation through violence against blacks, playing to fear, suspicion, and hatred against Haitian immigrants, accused of stealing crops and cattle from Dominican citizens.42 Though most every Dominican has some African heritage, identity is often defined through a blanqueamiento, a lightening, or self-hatred that denies this very part of their origins. Thus, to gain popularity in October 1937, Trujillo directed his troops to seize all suspicious persons and remedy their “border problem” by murdering approximately 15,000 thousand Haitians with machetes and guns. It was known as the Parsley Massacre, for the people said that Trujillo’s men held up a sprig of parsley and asked the accused men to say the name of the plant they held. If the poor sods pronounced the word with the Spanish trill or tap, the soldiers would know they were native Dominicans rather than French-speaking Haitians who pronounced it strangely and deserved thus to be executed on the spot.

By the Spring of 1947, the Caribbean Legion had assembled a small army in Cuba, plotting the overthrow of President Trujillo, preparing to launch their invasion from Cayos Confites and Romano, and benefiting from the open support of the Cuban government under the progressive leadership of Grau San Martín. Though estimates vary, the force was approximately 1,500 strong, composed of Cubans, Spanish Loyalists, American Veterans from World War II, and Dominican exiles, but they did not go to great efforts to dissimulate their intentions and soon attracted international attention.43 One of the members of the Legion was writer and future president of the Dominican Republic, Juan Bosch, and another was twenty-one-year-old Fidel Castro, and others were Hemingway’s friends, Paco Garay and Manolo del Campo Castro.44

President Trujillo protested the openness with which money was being contributed to the cause of this invading force assembling near his shores, so he convened an “International Justice Tribunal” to protect his state’s sovereignty. A newspaper report from Diario de la Marina implicated Hemingway specifically for his involvement in the plot, implying that he might be a target for the tribunal.45

Knowing many Legion members, like former Loyalists Roberto and Dr. José Luis Herrera Sotolongo (who knew Fidel Castro, the university student, at the time), Hemingway supported their cause, contributed money, and attempted to give advice, but felt frustrated by the group’s security, logistics, and priorities: “Hemingway gave some money for the Confites thing,” said Dr. Herrera Sotolongo, “But we heard he was going to be arrested, so I…got him a ticket for Miami…We got to the airport just a few minutes before the plane’s departure.”46

It was best for Ernest to take an impromptu trip via Miami to see family on Walloon Lake and to hunt in Sun Valley, without Mary, until the “Confites Affair,” as it would later be known, blew over and the cloud of accusations surrounding him dissipated like flurries across the Gulf. Shortly after his name appeared in the newspaper and his plane departed, the arrests began, and police came to the Finca and confiscated his hunting rifles. From afar, Hemingway ordered Gregorio Fuentes to dump the machine guns he kept aboard the Pilar into the sea under the cover of night.47 If Ernest had not had influential friends, such as Paco Garay, a former customs employee, he might not have escaped the affair unscathed.

When Trujillo threatened to attack Cuba to disperse the army and defend his interests, the American government pressured President Grau San Martín to arrest and detain Legion members before the conflict came to a head. Grau San Martín’s detractors suggested that his government saw the action in cynically opportunistic terms, for its purposes were impure: if he had started his career as a radical, he had become merely an opportunist in collaboration with Batista, and the invasion of Dominican Republic represented an opportunity to get rid of real radicals. His intention had always been leaving the Legion in the lurch: stranded on Cayo Confites awaiting promised armament or dying in an invasion without adequate support. The coup d’état failed, and President Trujillo ruled the Republic until 1961.

Laying low in a lodge in Ketchum, Idaho, to avoid arrest by authorities back in Havana, Ernest continued writing Islands in the Stream in November and December. With Mary joining, the couple would not return to Cuba until February. For Thanksgiving, Mary travelled to San Francisco to celebrate with her new friend, Pauline Pfeiffer, and two new stepsons, Patrick and Gregory. When his movie producer Mark Hellinger died in December, Ernest sent his condolences and half of his advance, returned to the deceased’s family in their time of loss and need, but requested a loan from Scribner’s to pay his taxes at the end of the year to the tune of $12,000.48 Thus, 1947 ended and 1948 began: bittersweetly in the company of good friends, Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, at a New Year’s Eve celebration in Trail Creek Cabin.

That winter, Ernest hosted other visitors in Idaho, like Juan Duñabeitia and Roberto Herrera as repayment for their loyalty with Patrick during his sickness. In March, Malcolm Cowley and his son stayed as guests for two weeks while interviewing Hemingway and preparing the article for Life magazine and another about Zelda Fitzgerald who died at the age of 48 when a fire engulfed her asylum in Ashville, North Carolina. As spring arrived, it was safe for Ernest to return to Cuba.

One Sunday in April, Papa was reading and relaxing in his favorite chair in a white guayabera, shorts, and moccasins, with René Villarreal, also in casual attire, hanging around the Finca on his day off. To receive the Duke of Windsor, Edward VIII, Ernest’s neighbor Frank Steinhart was throwing an extravagant black-tie party, which Mary was attending alone. Steinhart and Mary had both tried to get Papa to attend, but not wishing to waste his Sunday afternoon suffering in formal clothes in the sweltering tropical heat, he refused. The shrill ring of Mary and Steinhart’s calls broke the calm of his afternoon several times as they asked Papa to reconsider—yet he politely and firmly declined. When the Duke himself requested an audience with the famous writer, Papa finally surrendered, but he went just as he was, bringing René and his own martini bar, so that he would be able to have a decent drink during the ordeal. Soon the Duke of Winsor and his friends were rolling up their shirtsleeves and asking for martinis “like the one Hemingway was drinking.”49

During the same month, a twenty-one-year-old young man by the name of Fidel Castro was in Bogotá, Colómbia, to protest against the government of Mariano Ospina Pérez that had assassinated the liberal can

didate for president, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. The protest became a violent riot. At one point, the mob stormed police headquarters and destroyed much of downtown Bogotá. It would later be known as the “Bogotazo,” and was said to have given Castro a firsthand education in the power of an angry mob.

In June, the American editor and writer A. E. Hotchner (also known as “Ed” or “Hotch”) met Ernest Hemingway in El Floridita after phoning him to arrange a meeting for his article with the dubious title, “The Future of Literature”: from that moment, he would become a protégé and a friend helping Ernest to confront his deteriorating health. Hotch also profited significantly from this relationship in numerous articles and books.

In honor of his second son who had recovered and received an acceptance letter to Harvard University in the fall, Ernest organized a ten-day fishing trip in June 1948 to Cay Sal Anguillas and the Bahamas with Patrick, Gregory, Elicio Arguelles, and Mayito Menocal aboard Menocal’s large yacht, Delicias. That summer, after an extended sea trip with their father for his birthday, Patrick would travel to Europe before starting school. Accompanying them was the young son of a restaurant owner in Cojímar, Manolito, who impressed him by never becoming seasick and who would later serve as inspiration (along with his own sons) for the character of Manolin in The Old Man and the Sea.50

In August, Ernest’s lawyer, Maurice Speiser, would pass away suddenly. Following World War II came the Marshall Plan, the protection of an Israeli state and the resulting tensions, and the Cold War—where Ernest was identified with the code name “Argo” as a potential ally of the Soviets, sympathetic and willing to help their cause. At the end of the summer, he conscripted Roberto Herrera Sotolongo’s support to take up a “birthday purse” for his barroom pal and lover, Leopoldina Rodríguez.51

CHAPTER 10

A Middle-Aged Author’s Obsession with a Young Italian Aristocrat (1947–1951)

Arriving late and fatigued to the port of Havana, Enrique Serpa held the hand of Clara Elena, his twelve-year-old daughter, as he crossed from the road between the parking lot and the docks. Though he was not entirely sure where his group would be, he soon heard the clinking glasses, the gags, and the guffaws, a few yards away. There was then the heavy belly-chuckle and singing of his literary counterpart. Departing for Italy on September 7, Hemingway had organized an impromptu “departure party” for himself before setting sail, and he had invited Serpa. Ernest hugged Enrique so tightly as he arrived to the party that he thought he heard his bones being crushed.1

The name of the ship was Jagiello, built in Germany, but now manned by a Polish crew. Serpa’s daughter, Clara Elena, remembered a folkloric display aboard, including a doll with a Polish dress that she had been admiring. When Hemingway saw her eyeing it, he announced that he would buy it for her. Because the doll was part of the boat’s display, it was not for sale. Seeking out his “old friend ‘the Commissioner,’” Hemingway insisted that he be allowed to buy it for Serpa’s daughter; “for religious reasons,” they could not float across the ocean with such a totem aboard. Hemingway’s friend, Cuban bureaucrat Paco Garay, offered the captain’s assistant “special permission” to sell the doll without tax imposed.2 In due course, the merry band again got its way, and Hemingway purchased the doll. In their enthusiasm, all the members of the party signed the doll and gave it to Clara Elena. Nearly an adolescent at the time and ambivalent to the fact that there were famous writers in the group, Clara Elena related later that she despised the doll whose charm the group desecrated, its face and limbs marred with the signatures of drunken strangers.3

The Hemingways disembarked at Genoa at the end of September. Met by Italian writer, journalist, translator, and critic Fernanda Pivano, who had been translating the manuscript of Adio alle armi in 1943, the Hemingways were welcomed in Italy where they made themselves at home for a season in another land.4 At the beginning of November, the Hemingways moved from the Venice Hotel Gritti to the Locando Cipriani on Tocello Island, quiet, picturesque, yet only a half hour by speedboat from the action. Celebrities in their “bella macchina americana,” they enjoyed la dolce vita as they stayed in Venice, visited Stresa, Como, Bergamo, and retreated into the mountains of Cortina d’Ampezzo to ski.5 Though Mary had the misfortune of breaking her ankle on the slopes, the Hemingways became friends with four noble families during that trip to Italy (Franchetti, Di Robilant, Kechler, and Ivancich), with whom they would cultivate relationships in succeeding years.6

Back in Cuba, on October 10, Carlos Prío Socarrás became the nation’s president when Grau San Martín turned over the reins to his protégé, a fellow member of the “Authentic Party,” which was by then widely mistrusted due to the era’s rampant corruption and gangsterism. Under Prío’s administration, Cuba would create the National Bank of Cuba (1948) as well as the Agricultural and Industrial Development Bank (1951) as the government passed several initiatives designed to decentralize Cuba’s economy and diversify its agricultural production.7 Remaining in power until 1952, Prío would come to be known as el presidente cordial,8 for in the midst of criticism, he advocated civility over harsh words and violent protests, but his administration, like that of Grau San Martín, would be clouded by discontent and allegations of corruption.

* * *

—

As the invited guest of the Franchettis one weekend at the beginning of December 1948, Ernest Hemingway was hunting at their lodge near Latisana, to the northeast of Venice. And he met Adriana Ivancich. Apologizing for the Allied bombing of her family home, he offered her a swig of whiskey from his flask.9 Later, after a rainy day of hunting, he came across her again while she was drying her long dark hair beside an open fire and went barmy as she revealed her beauty, breeding, and other charms. Hemingway wrote afterward that “something like lightning struck at the crossroads in Latisana in the rain,” so he met the girl he nicknamed “Black Horse” for lunch at the Gritti Palace soon after his return to Venice.10 Her dark, long, and luxurious hair, her smooth, olive-brown skin, her intense green eyes, her sharp aquiline nose, her grace, her elegance, her innocence, and her intelligence, came together in the form of a charming girl of just eighteen years of age who bewitched Hemingway, and soon turning fifty, would cause him to behave like a lovestruck buffoon.

F. Scott Fitzgerald had superbly and rather evilly prognosticated that each major work by his friend Ernest Hemingway would require a new wife, as a muse to excite his creative fires. In fact, Ernest pursued a new love, and a new marriage, during each of his novels: Hadley, A Sun Also Rises; Pauline, A Farewell to Arms; Martha, For Whom the Bell Tolls; and Mary, The Old Man and the Sea. This time, however, the girl he would fall for and pursue would ultimately reject, perplex, pervert, and hurt him, resulting in a novel expressing his physical and literary impotence.11

Although Dora Ivancich cordially received the Hemingways and their offer of friendship, instinct, convention, and perhaps revulsion prohibited her from permitting her daughter to be left alone with that randy old man.12 Whereas Hemingway’s powers of enchantment were significant, they were unable to overcome the societal structure of “La Torre Bianca” that engendered and protected such a Venetian jewel. La torre bianca (The White Tower) became the title of Adriana’s memoirs, the focus of which was a fond and sorrowful reflection on her time with Hemingway.

Observing her husband and Adriana, “busily launching a flirtation,” Mary wrote later that she was more concerned for Ernest’s feelings than her own, for he was weaving a mesh in which he might entangle himself and cause himself pain. In the interim, in the mountains near Cortina, Ernest began a short story about duck hunting in Venice that grew into the novel Across the River and into the Trees. While in Italy, he also wrote a nostalgic article about Cuba for Holiday magazine called “The Great Blue River.”

When Ernest unexpectedly contracted a severe eye infection, doctors feared it would cause damage to his brain and evacuated him to a hospital in Padua where he would spend ten days before returning to Venice. The

re, they would meet Adriana Ivancich’s brother, Gianfranco. Gianfranco had already received an offer of employment in Havana with Sidharma Shipping Agency.13 Enamored with his sister, Ernest became fond of the boy—who had seen combat during the war—befriended him, and offered him a place to live in their beloved Cuban home.14

* * *

—

The article “The Great Blue River” recalled his encounter with Cosmopolitan magazine reporter Ed Hotchner, who apologized for being sent down to Havana “on the ridiculous mission of interviewing [him] regarding ‘The Future of Literature.’” If he could just send a few words of refusal, he said, “it would be enormously helpful to ‘The Future of Hotchner,’” and he would be on his way.15 Early the next morning, the phone rang in the young reporter’s hotel room:

“This Hotchner?”

“Yes.”

“Dr. Hemingway here. Got your note. Can’t let you abort your mission or you’ll lose face with the Hearst organization, which is about like getting bounced from a leper colony. You want to have a drink around five? There’s a bar called La Florida [sic]. Just tell the taxi.”16

Arriving on time, Ed Hotchner stood inside the famed Floridita bar, beside the slab of mahogany that ran the length of the room, peering at the photographs of the author and his wife on the wall. Soon the man himself burst through the double doors of the entryway, and as Ernest Hemingway stopped to talk to one of the musicians in fluent Spanish, something about the man hit the twenty-seven-year-old reporter: “Enjoyment: God, I thought, how he’s enjoying himself! I had never seen anyone with such an aura of fun and well-being. He radiated it and everyone in the place responded.”17 It was a portrait of the man in a moment in time, yet it was the genius that seemed to defy portrait, or time, itself: “He had so much more in his face than the photographs.”18

Ernesto

Ernesto